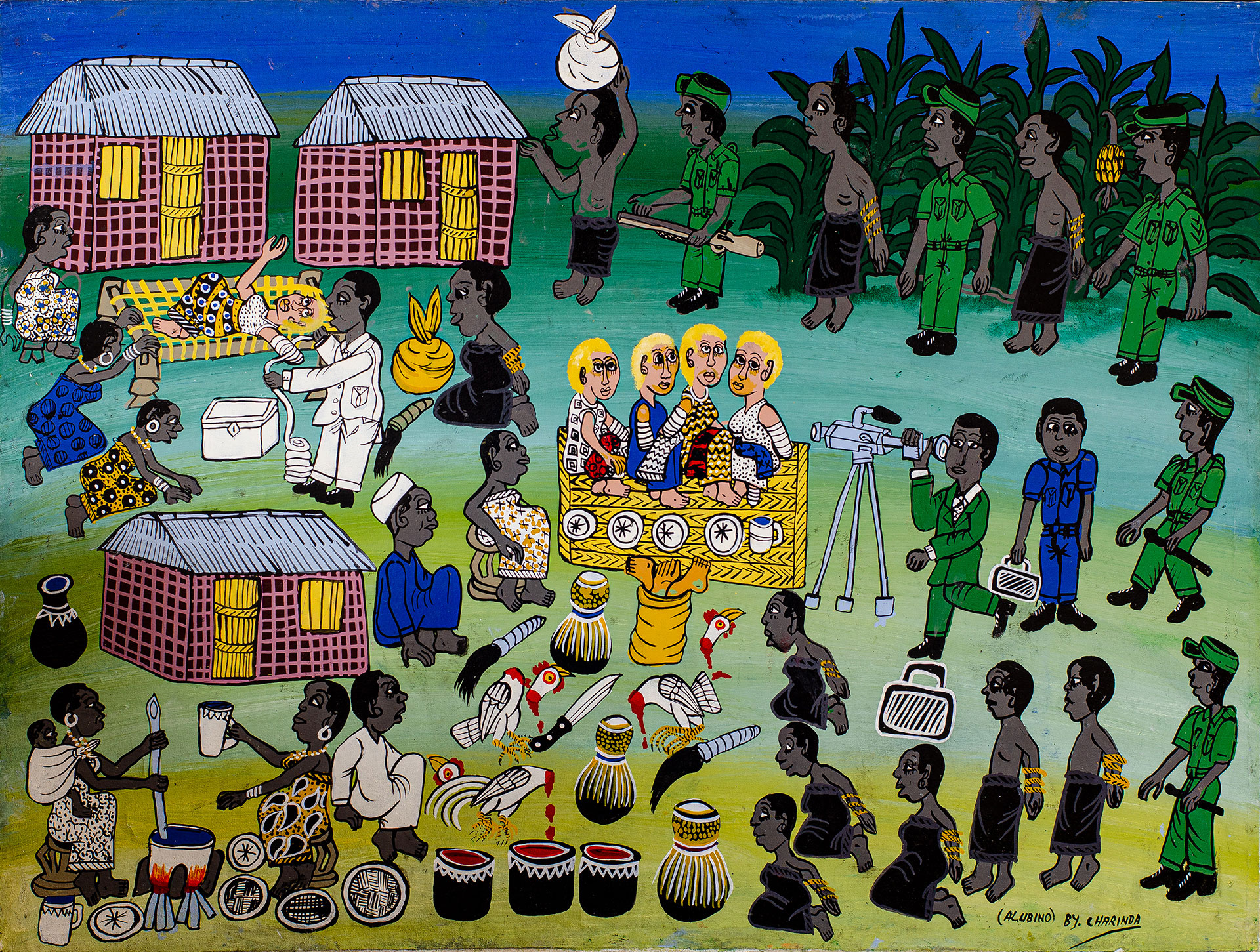

Charinda, 2017

Acrylic on canvas - 98.8х74.5

Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

Acrylic on canvas - 98.8х74.5

Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

How does the traveller see it?

(Fragment of a post from a Facebook page)

What do I like about African art?

It’s in the Mother Continent that I find the most honest paintings. Why do I feel that way? There is always something happening in the picture. And I, as a traveller, am eager to figure out what exactly that is. The seller – ideally, the artist behind the work – talks about what’s going on in the picture. And this exchange is in itself special; you’re buying a riddle where only the artist and, now, you, know the answer. At some point, I wanted to share some of these riddles with the world. I bought this canvas – which was my cover photo on Facebook for a long time – in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

The title of the painting is Albinos. It depicts an operation in which police apprehend criminals involved in the trafficking of albinos and albino body parts. Many of the albinos are already missing arms and legs. Prior to 2009, albinos were simply killed, but after they began hanging criminals, those criminals switched to cutting off limbs; the punishment was less severe. Witches make potion from the blood of roosters and limbs from unfortunate victims of the somewhat barbaric belief that many Africans have in witchcraft. They believe that this concoction is a panacea for all illnesses. They also believe that if you eat dried genitals, you will be cured of AIDS. When you compare this to what Zulus in South Africa believe – that sex with a virgin is a similar cure for AIDS – it’s hard to say which is worse. A policeman documents the crime with a camera. A doctor provides aid to the victims.

The name of the artist is Charinda – I bought two more works from him, in the style of Tingatinga, at his workshop. A few years later, in London (at the British Museum!!!), I saw a piece of art similar in style to this one. Imagine my surprise when I read the name of the artist, Charinda! Art connects countries and continents in such a unique way.

It’s in the Mother Continent that I find the most honest paintings. Why do I feel that way? There is always something happening in the picture. And I, as a traveller, am eager to figure out what exactly that is. The seller – ideally, the artist behind the work – talks about what’s going on in the picture. And this exchange is in itself special; you’re buying a riddle where only the artist and, now, you, know the answer. At some point, I wanted to share some of these riddles with the world. I bought this canvas – which was my cover photo on Facebook for a long time – in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

The title of the painting is Albinos. It depicts an operation in which police apprehend criminals involved in the trafficking of albinos and albino body parts. Many of the albinos are already missing arms and legs. Prior to 2009, albinos were simply killed, but after they began hanging criminals, those criminals switched to cutting off limbs; the punishment was less severe. Witches make potion from the blood of roosters and limbs from unfortunate victims of the somewhat barbaric belief that many Africans have in witchcraft. They believe that this concoction is a panacea for all illnesses. They also believe that if you eat dried genitals, you will be cured of AIDS. When you compare this to what Zulus in South Africa believe – that sex with a virgin is a similar cure for AIDS – it’s hard to say which is worse. A policeman documents the crime with a camera. A doctor provides aid to the victims.

The name of the artist is Charinda – I bought two more works from him, in the style of Tingatinga, at his workshop. A few years later, in London (at the British Museum!!!), I saw a piece of art similar in style to this one. Imagine my surprise when I read the name of the artist, Charinda! Art connects countries and continents in such a unique way.

What does the expert say?

We see a rectangular, horizontal format that one could refer to as “panoramic”. Two-dimensional features, an absence of linear and aerial perspectives. The backdrop functions like that of a theater set, and no real surface is outlined. The colors are clear (with the exception of the background, in which gradients can be found).

We can discern a clear segmentation of people by color: the criminals (10) are dressed in black, the police (6) in green, the doctor in white, the shaman in blue, a criminal investigator also in blue, and the shaman’s assistant in white, while the remaining figures wear multicolored clothes. A similar technique is used in iconography, a form of art that this painting also resembles by virtue of its narrative element: the canvas shows us people engaged in actions and lays out a clear plotline.

The compositional center is the floormat on which four albino amputees (women) are sitting. In front of them we see limbs sticking out of a yellow sack; we see another one with a yellow knot lying next to a criminal woman who has her hands tied. I reckon that this sack also contains body parts based on how faithfully the artist employs color segmentation.

The painting can be split into two parts by a vertical line that passes through the physical center. The left and right sides are looking at the albinos, and this focuses the viewer’s eye on the narrative being told. All our attention is on the bright patch of color in the center – a patch of mutilated and miserable humans.

In the top left corner, we see the healing process at work, which stands in contrast to the death ritual depicted at the bottom involving three headless birds (perhaps an homage to how things were before 2009, when albinos were simply killed for profit).

Just left of center sits a shaman (passive criminal) in blue clothing – he is monitoring the right side of the canvas, where a policeman is capturing the scene on tape. It’s a tacit stand-off, one that is both legal and technological in nature. The superstitious shaman, who lives off of human ignorance and belief in the supernatural, faces a policeman with his camera (a high-tech item) who upholds the Law – which, like technology, is a mark of civilization. This is a stand-off between the old world and the new world in developing countries.

The work, incidentally, lays out the entire criminal system – the chain all the way from contractor to end customer.

Unlike, for example, Francisco Goya’s painting “The Third of May 1808”, where it’s as if the viewer is a witness, looking at the scene through a window, “Albinos” creates a sort of map in which we look down at sequential actions from above – there is no factor distracting us. On the one hand, traditionalism is present here in the relativistic depictions, while on the other hand this traditional approach does the best job at bringing the issue at hand to light. Minimalism puts the emphasis squarely on the message the artist wants to get through to the viewer.

Instead of a conclusion: the albinos serve, of course, as the main imagery in this piece of art, but they are more like the consequence of a broader cultural and civilizational moment. The painting is not a mere illustration; it is loaded with much more substance. Whether this type of evildoing could take place in a country where people can make a living without having to risk their lives is a rhetorical question, and it’s a question the artist asks of us. He sees the world changing, shows that change in elements of this painting, but he understands that it is not sufficient to provide help after the fact (eg. the healing scene in the top left) – his country itself needs to be healed. The dead birds must become a thing of the past.

Roman (Miller) Miroshnichenko, artist, art populariser

We can discern a clear segmentation of people by color: the criminals (10) are dressed in black, the police (6) in green, the doctor in white, the shaman in blue, a criminal investigator also in blue, and the shaman’s assistant in white, while the remaining figures wear multicolored clothes. A similar technique is used in iconography, a form of art that this painting also resembles by virtue of its narrative element: the canvas shows us people engaged in actions and lays out a clear plotline.

The compositional center is the floormat on which four albino amputees (women) are sitting. In front of them we see limbs sticking out of a yellow sack; we see another one with a yellow knot lying next to a criminal woman who has her hands tied. I reckon that this sack also contains body parts based on how faithfully the artist employs color segmentation.

The painting can be split into two parts by a vertical line that passes through the physical center. The left and right sides are looking at the albinos, and this focuses the viewer’s eye on the narrative being told. All our attention is on the bright patch of color in the center – a patch of mutilated and miserable humans.

In the top left corner, we see the healing process at work, which stands in contrast to the death ritual depicted at the bottom involving three headless birds (perhaps an homage to how things were before 2009, when albinos were simply killed for profit).

Just left of center sits a shaman (passive criminal) in blue clothing – he is monitoring the right side of the canvas, where a policeman is capturing the scene on tape. It’s a tacit stand-off, one that is both legal and technological in nature. The superstitious shaman, who lives off of human ignorance and belief in the supernatural, faces a policeman with his camera (a high-tech item) who upholds the Law – which, like technology, is a mark of civilization. This is a stand-off between the old world and the new world in developing countries.

The work, incidentally, lays out the entire criminal system – the chain all the way from contractor to end customer.

Unlike, for example, Francisco Goya’s painting “The Third of May 1808”, where it’s as if the viewer is a witness, looking at the scene through a window, “Albinos” creates a sort of map in which we look down at sequential actions from above – there is no factor distracting us. On the one hand, traditionalism is present here in the relativistic depictions, while on the other hand this traditional approach does the best job at bringing the issue at hand to light. Minimalism puts the emphasis squarely on the message the artist wants to get through to the viewer.

Instead of a conclusion: the albinos serve, of course, as the main imagery in this piece of art, but they are more like the consequence of a broader cultural and civilizational moment. The painting is not a mere illustration; it is loaded with much more substance. Whether this type of evildoing could take place in a country where people can make a living without having to risk their lives is a rhetorical question, and it’s a question the artist asks of us. He sees the world changing, shows that change in elements of this painting, but he understands that it is not sufficient to provide help after the fact (eg. the healing scene in the top left) – his country itself needs to be healed. The dead birds must become a thing of the past.

Roman (Miller) Miroshnichenko, artist, art populariser

And what do you think?